Last updated on November 28, 2025

Talent identification is a huge topic in sports, particularly soccer.

A 2022 paper in the German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research suggests that it may be more beneficial to look for interest before talent.1

The Background

“Generally, a talent is described as a person who possesses outstanding potential in a particular domain, either over a range of activities and situations, or within a specialized and narrow field of expertise.”2

“In relation to sports, talents describe people who demonstrate exceptional ability compared to reference groups of similar biological developmental stage and similar lifestyle habits and the training already realized, which indicates that he or she will be able to achieve exceptional athletic performance in the long-term.”3

It has become clear “that top performance at a young age in particular does not always mean top performance at senior level, but that the paths of athletic talent are manifold.”4

Translation: Talented youth athletes don’t always go pro, and when they do, there’s as many paths as there are pros.

“Talent detection aims to motivate children to choose one or more sports in accordance with

their own personality traits and which can take place both transitively and intransitively.”5

Translation: Talent identification helps young athletes find sports in which the athlete is interested (not the parents, coaches, clubs, etc.). The athlete can pick the sport, or adults can help.

“For the purpose of understanding and mapping the development from athletic novice to elite performer, there are numerous models for long-term performance building. . . . In summary, the basic assumption of the existing models is that there is a general interest in sports or a specific sport.”

Translation: There are a number of athlete development models. All of them assume (many times incorrectly) sufficient interest to pursue performance training and purposeful practice.

The Proposition

“The listed models do not consider the phase of entry into the sport (talent detection). How the process of detection turns out is open because first the discovery phase should lead to

mastering and accompanying current situations. The measures of talent detection should lead to ‘getting interested in an area’ even before talent identification occurs.”6

Translation: People selecting youth athletes for circumstances involving more than recreational play should make sure each athlete is truly interested in pursuing the sport more seriously (through the athlete’s actions, not words – and not the parents’ words either).

Analysis

“Several studies show that, at least in the retrospective view, early specialization does not favor the development of elite athletes and before adolescence, diverse sports participation is more important.7 . . . In general, it seems important to create positive experiences (not only through a variety of sports, but also through versatile experience within a sport and diverse forms of mediation) in order to offer every child, if possible, a space in which they can find themselves. This will not only generate interest and develop positive attitudes towards sports in general, but it could possibly also reduce the dropout rate.”8

On the topic of Anders Ericsson’s delberate practice:

Based on Ericsson et al. (1993) the path of early specialization offers optimal

starting conditions for 10 years of deliberate practice (DP). These have been assumed to be the amount of practice years needed to achieve peak performance, particularly in the arts. DP was operationalized as any training activity that (a) is undertaken with the specific purpose of increasing performance (e.g., not for enjoyment or external rewards), (b) requires cognitive and/or physical effort, and (c) promotes skill development (Côté, Allan, Turnnidge, & Erickson, 2020). These number[s] must not be considered too strict in a sporting context, depending on the type of sport. The central assumption of the deliberate practice model, that the personal investment of time and effort gives athletes little pleasure and is only sustained because of sporting success, must also be critically questioned. Thus, the direction of this cause–effect hypothesis can also be interpreted in the opposite way: according to the sport commitment theory (Scanlan, Carpenter, Simons, Schmidt, & Keeler, 1993) competitive sport training is pursued precisely because it is enjoyable (Hohmann, Lames, Letzelter, & Pfeiffer, 2020). This in turn presupposes interest and motivation.

Translation: Performance pathways and purposeful practice are for athletes who truly want them because if their earnestly-held internal interest and motivation.

“As reported by Barth and Emrich (2020),9 the promotion of a young talent should be organized in such a way that at even in the end of an unsuccessful promotion process (as a loser on the criterion of sporting success), the young talent does not feel that the time has been misinvested. This requires a pedagogically oriented design and management of the

training process, which emphasize autonomy, self-control, self-reflection and enrichment, which ‘refers to the rich variety of play, physical activities, games and sports, that children and youth experience prior to (as well as during) the specialization phase in talent pathways.'”10

Translation: Training for talented youth athletes should be designed and managed so as to inlcude multiple sports and to allow the athletes to have a say in what they do and how they do it.

Summary of the Findings

“In order to take a path in sports, it is important to have an interest in the sport. This interest can then be solidified in further steps (perhaps even in the talent development process) and mature into lasting interest.”

Translation: True interest in pursuing sporting excellence is necessary before undertaking anything beyond recreational play. This is the best way to encourage continuing interest sufficient to promote elite athlete development.

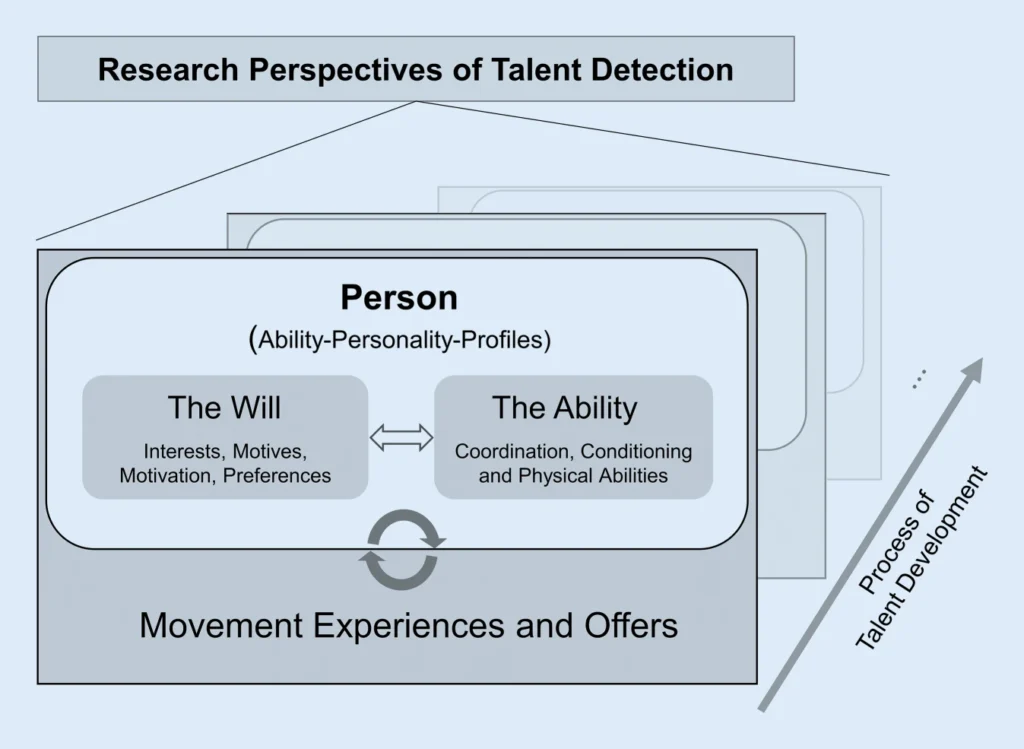

“The central element of the present proposal is the person (athlete) who has a certain ability–personality profile. This profile includes the two areas of the will and the ability. When creating suitable (movement) offers for a person, both the abilities and the will should be considered. At the same time, previous experiences of different offers in turn result in characteristics of the abilities and the will. Thus, it is not only important to consider the current individual ability–personality profiles of a person, but in the field of talent development it is equally important to gather experiences to form these profiles (interest, motivation, etc.). Thus, over the time of the talent development process, there are always changes in the ability–personality profile and thus changes in the Movement Experiences

and Offers.”

Translation: An athlete has a unique mix of skills and personality traits. This mix includes two key parts – ability and will. When choosing sports, both the athlete’s abilities and interest should be considered. At the same time, the activities a person tries will shape their abilities and interest. So, it’s important not only to look at an athlete’s current skills and interest, it is also important to give young athletes experiences that help increase interest. Over time, as an athlete develops, their mix of skills and interests will keep changing, and so also may the types of activities that best fit them.

Conclusion

“Although talent development is a process and predictors should be viewed dynamically

over the long term, entry into sport is the start of any athletic process. Already at this point, numerous factors of willingness and ability play a role, which at best are examined and considered together with their arrangement. To inspire enthusiasm for sports, interest is of

great importance.”

Translation: Interest is the first step to performance sport.

Some Insights

Talent doesn’t always equal competitive interest. Many talent identification models assume that a talented youth athlete is sufficiently interested in the sport to pursue the sport in the performance context. This is not always the case. Interest is cultivated over time.

Interest before committment. True interest is necessary before any youth athlete is truly prepared to train and play in a performance environment.

Diversitication beats early specialization in young athletes. Children who play multiple sports at young ages often have the best outcomes.

Performance pathways and deliberate practice aren’t for all athletes. They are for interested athletes.

1 Spies, F., Schauer, L., Bindel, T., & Pfeiffer, M. (2022b). Talent detection—importance of the will and the ability when starting a sport activity. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 52(4), 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-022-00796-0 (“Spies, et al.”). The paper can be found here.

2 Spies, et al. (citing Williams, M. R. (2000). The war for talent: Getting the best from the best. London: Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development).

3 Spies, et al. (citing Baker, J., Cobley, S., Schorer, J., & Wattie, N. (Eds.). (2017). Routledge Handbook of talent identification and development in sport. New York: Routledge).

4 Spies, et al. (citing Güllich, A., Macnamara, B.N., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2021). What makes a champion? Early multidisciplinary practice, not early specialization, predicts world-class performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620974772).

5 Spies, et al. (citing Pion, J. (2015). The Flemish Sports Compass: From sports orientation to elite performance prediction (Dissertation). Ghent University, Ghent); Vaeyens, R., Lenoir, M., Williams, A.M., & Philippaerts, R.M. (2008). Talent identification and development progammes in sport. Sports Medicine, 38(9),703–714).

6 Spies, et al. (citing Pion, J. (2015). The Flemish Sports Compass: From sports orientation to elite performance prediction (Dissertation). Ghent University, Ghent)).

7 Spies (citing Barth, M., Emrich, E., & Güllich, A. (2019). A machine learning approach to “revisit” specialization and sampling in institutionalized practice. SAGE Open, 9(2), 215824401984055. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019840554; Kliethermes, S.A., Nagle, K., Côté, J., Malina, R.M., Faigenbaum, A., Watson, A., et al. (2020). Impact of youth sports specialisation on career and task-specific athletic performance: A systematic review following the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM) Collaborative Research Network’s 2019 Youth Early Sport Specialisation Summit. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54(4), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101365).

8 Spies, et al. (citing Alfermann, D. & Stoll, O. (2017). Sportpsychologie: Ein Lehrbuch in 12 Lektionen [Sports psychology: a textbook in 12 lessons] (5th edn.). Sportwissenschaft studieren, Vol. 4. Aachen: Meyer&Meyer; Singh, A., Voigt, L., & Hohmann, A. (2015). Konzepte

erfolgreichen Nachwuchstrainings (KerN) [Concepts of successful junior training]. Leistungssport, 2,11–16).

9 Barth, M., & Emrich, E. (2020). Talententwicklung im Fördersystem des Nachwuchsleistungssports [Talent development in the support system of young high performance sports]. In C. Breuer, C. Josten &W. Schmidt (Eds.), Vierter Deutscher kinder- und Jugendsportbericht [Fourth German children’s and youth sports report] (pp. 225–248). Schorndorf:Hofmann-Verlag.

10 Spies, et al. (quoting Ribeiro, J., Davids, K., Silva,P., Coutinho, P., Barreira, D., & Garganta, J. (2021). Talent development in sport requires athlete enrichment: contemporary insights from a nonlinear pedagogy and the athletic skills model. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.), 51(6), 1115–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01437-6).

Comments