Last updated on December 15, 2024

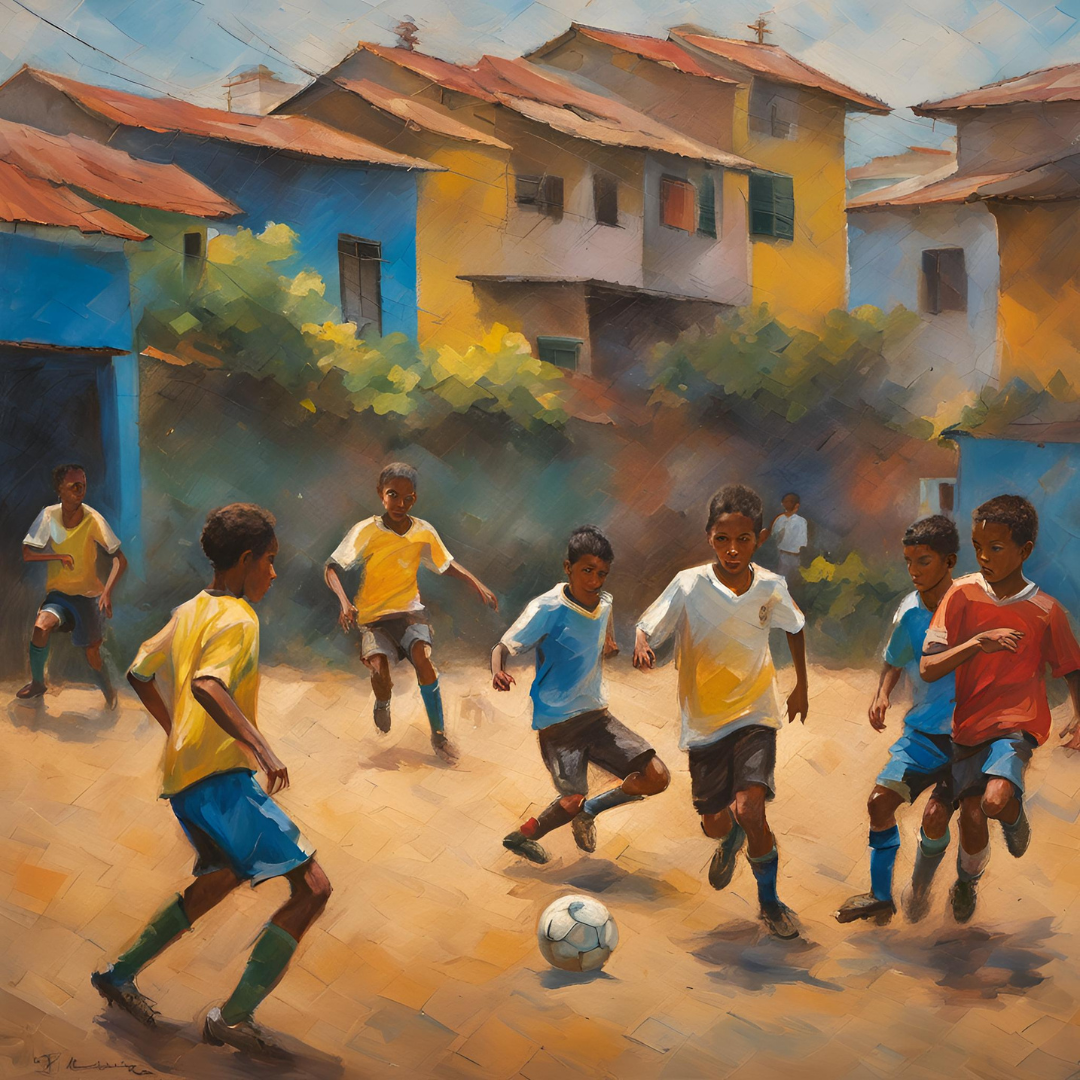

In Brazil, soccer is more than just a sport—it’s an integral part of the culture. Many young players grow up playing the game in informal settings, like streets, beaches, and dirt fields. These environments are far from perfect, often featuring uneven surfaces, obstacles (like rocks and weeds), and makeshift goals (and sometimes makeshift “balls”). Young players still manage to develop exceptional skills, however.

A key concept in Brazilian soccer is “unstructured play.” Kids play spontaneous games (“peladas”), with no coaches, few rules, and constantly changing teams and conditions. This play encourages creativity, adaptability, and problem-solving. Players have to deal with the game’s unpredictability.

Zico, one of Brazil’s most legendary players, recalls spending entire days playing balls sometimes made of socks or rubber. He would throw the “ball” against a wall and practice controlling it, often alone in his room. Zico credits these unstructured, self-driven sessions as fundamental to developing his reflexes and ball control, which later defined his career on the field.

Similarly, Sócrates,1 one of the top 125 FIFA players in history, began his soccer journey on the streets with nothing more than an avocado seed as a ball. He played in orchards with irregular surfaces, surrounded by trees. Sócrates credited learning to play in these conditions as excellent training because it forced him to develop a range of abilities, like avoiding injuries while focusing on both the ball and the game. This environment required him to be aware of his surroundings, such as the roots of mango trees that could trip him up, teaching him to balance his attention between the game and the obstacles around him.

Garrincha, widely regarded as the best dribbler in football history and a key player in Brazil’s World Cup victories in 1958 and 1962, also reflects on his early years playing on rough, uneven surfaces. He recalls dribbling the ball barefoot, a significant challenge that taught him how to maintain control on tricky terrain. Garrincha often practiced on a slope, learning to dribble without letting the ball roll down. These informal sessions on challenging surfaces were crucial in developing his unmatched dribbling skills.

These are the conditions in which youth players in Brazil often play:

Where

Pelada can take place anywhere—on streets, beaches, courts, dirt fields, formal fields, backyards, or any available space. The type of surface varies a lot, and this variability icontributes to developing different soccer skills.

Field Size

The size of the field is highly variable. The field can be (and often is) adjusted by the players or according to the specific features of the playing area.

Equipment

Players often use whatever is available. Stones, shoes, or bags are used as “goalposts,” and the game can be played with basically anything that can be kicked. Some players play barefoot, and uniforms might consist of “shirts versus skins.”

Teams

Teams are adaptive and versatile, with the number of players adjusted to maintain an ongoing challenge, fun, and balanced competition. Players of different ages, genders, and skill levels often play together.

Coaching

There are no coaches. Learning happens among the players, who typically try to reproduce the skills performed by elite players or their more skillful friends.

Tactics and Positions

There are no fixed positions or agreed-upon tactics. Players can change positions or functions multiple times during a game, allowing them to learn and adapt to different roles on the field.

Players’ “Why”

Players try to reproduce famous players’ “moves”, try out new skills, have fun, and to compete against (and best) others around them. Winning is not the #1 thing.

When Does It End?

The game continues until a certain number of goals have been scored, a set time is reached, or players get tired or lose interest. The game might start, stop, and restart multiple times throughout the day, with the teams and conditions often changing after breaks.

Can This Happen in the US?

Would this type of unstructured play help improve soccer in the United States?

Most definitely.

Can this type of unstructured play ever become part of the soccer culture in the United States?

Only time will tell. It will take a substantial change in the US’ soccer culture for this type of unstructured play to take hold.

The information in this post is based on an academic paper entitied “The Role of Ecological Constraints on Expertise Development” by Duarte Araujo, et al. (Talent Development & Excellence Vol. 2, No. 2, 2010, 165–179).

The paper can be found here.

- Socrates was the player I “wanted to be” when I was young. ↩︎

Comments